Did the Ottomans massacre 800 Christians in Otranto?

11/05/2020The most controversial and unfortunate event in the Ottoman campaign for the control of southern Italy, the Conquest of Otranto, is certainly the question of the “Martyrs of Otranto”, so called the 800 Catholics who, according to some narratives, died in Turkish hands for not accepting a forced conversion to Islam.

1470-1554).

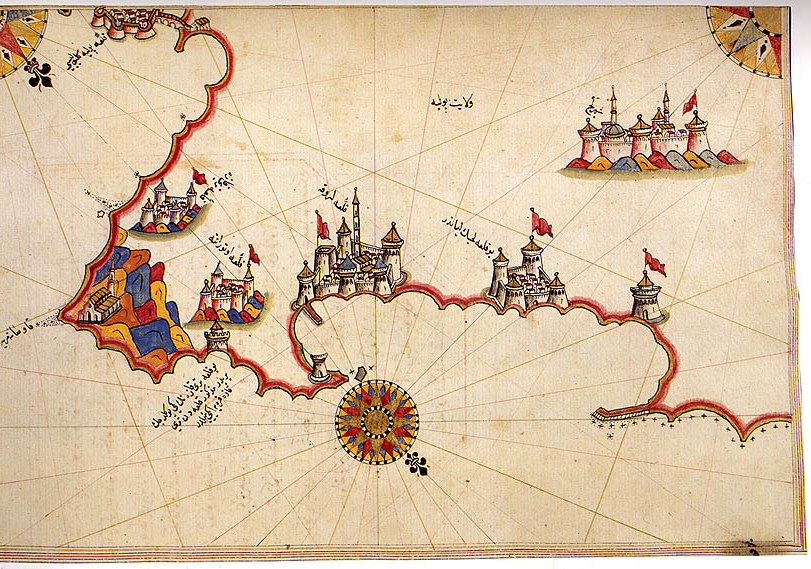

Beginning with the campaign that sought to conquer Rome itself and punish Naples for the help provided to the slave-owning pirates of the Knights of Rhodes who plundered the trade and pilgrimage routes in the eastern Mediterranean, about 20 thousand men led by the Serbian / Albanian Gedik Ahmed Pasha landed on the Italian coast in the summer of 1480, seeking to take the port of Otranto and use it as a naval base for other operations in the Italian Peninsula.

Upon the arrival of the Ottoman troops, the local population entrenched themselves along with their garrison in the citadel of Otranto, and for 15 days the Ottoman forces were in a painful siege. Two offers of peaceful surrender sent by the Turks were refused by the defenders, the second resulting in the Ottoman emissary returning to the camp dead and riddled with arrows. After the walls finally fell in the siege, the Ottoman forces entered the city, and according to later Christian narratives: they went from house to house, emptying everything and setting fire, killing 12 thousand people in the fighting, enslaving five thousand, and transforming the city cathedral in a mosque.

However, according to them, 800 of the captives would have been selected to “convert to Islam or die”, and when they denied it, they would have been killed by the turkish swords. The scene has been part of the the Catholic imagination for centuries. Paintings, sermons and even a church was erected in the city on which altar would be the skulls of the 800 martyrs that the Turks have executed for “not denying Christ”.

However, this narrative, as demonstrated by modern historians, has some flaws. First, the official policy of the Ottoman Empire, even more so under Mehmet II, was one of relative tolerance for civilians and Christian clergy in conquered regions, with forced conversions never being a common practice. By way of example, 17 years before the Otranto campaign in 1463, the sultan had issued the Ahdname of Milodraž, forbidding any attack on the Bosnian Franciscans or other Christian civilians by extension, just there across the Adriatic Sea at 666.6 km from Otranto, under penalty of death to anyone who disobeyed it. The Sultan’s decree said:

I, Sultan Mehmed Han, command that: No one should disturb or harm these people and their churches. Let them live in peace in my empire and let these people, natives or immigrants, live safely and freely. Let them return to their homelands within the borders of my empire and live and establish their monasteries. No member of the royal family, nor my neighbors, nor my servants, nor the citizens of this empire will violate the honor or hurt these people. No one is allowed to take their lives, their property or their churches, insult or harm them, and even if these people bring citizens of other countries into my kingdom, these new people will enjoy the same rights. I swear by Allah, the Creator and Lord of heaven and earth, by the Messenger of God, our Prophet Muhammad (may Allah’s peace and blessings be upon him), by the 124,000 Prophets, and by the sword I am using, that none of my citizens will contradict this order, being loyal to me and followers of my commandments.

Second, the sale of post-siege captives was an infinitely more profitable activity for a campaigning army than simply killing 800 men for “not accepting Islam”, as they could row their galleys, serve as hostages for ransoms and in the very Ottoman army had Christian mercenaries.

Contemporary sources at the time speak of the execution of soldiers and civilians who participated in the resistance during the siege, but do not mention “forced conversion” at any time as presented in the works of Nancy Bisaha and Francesco Tateo. The analyzes suggest that, in an unknown number, men may have been executed as a punitive measure, devoid of religious motivations, something required to punish the local population for the strong resistance they presented, which delayed the Turkish advance and allowed the king of Naples to strength the local fortifications, ruining the entire Ottoman campaign, which also had to be abandoned 13 months later due to the sultan’s death in May 1481.

Intimidation, a warning for other populations not to resist, may also have entered the attackers’ plans, since the two attempts to negotiate a peaceful surrender were rejected by Christian defenders, answered with the messenger’s death. This is even the justification presented by the Turkish chronicles themselves, such as that of Ibn Kemal. The sources that speak of executions of Christians for rejection of Islam and attempted forced conversion, in addition to much later, are rich in “details”, exaggerated and divergent in numbers, with dialogues between martyrs, executors, miracles, and so many other things that make them somewhat historically unlikely, as they are nothing but a strong dramatization for political propaganda of the time.

After deciphering contemporary documents referring to the case in the state archives in Modena, researcher Daniele Palma, who wrote an entire book about what happened, suggests that some executions occurred as a result of a diplomatic failure to raise funds for captives. The records refer to bank transfers and payment negotiations for the rescue of prisoners after the siege of Otranto, in which Turks and the Christian nobility in the neighborhood dealt with the release of certain notables. With a typical ransom of 300 duchies (about three years of earnings for a normal family), Palma says that the prisoners executed by the Turks were probably farmers, pastors and others too poor to pay for the ransom, and that they were in no way killed because “Rejected Muhammad.”

Ultimately, the execution of prisoners after a long siege was a sad tactic of psychological warfare, an occasional occurrence in clashes between Christians and Muslims. In the same decade in which the Ottoman invasion of Otranto took place in Italy, on the other Mediterranean Peninsula, the continuous Christian invasion of the Emirate of Granada by the combined forces of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, saw macabre scenes surrounding the cities of Alhama and Malaga, where Muslim civilians were not only executed in droves and sold as slaves, but also put alive on poles as darts targets in celebrations of Catholic armies. However, the emphasis on the typically Christian culture of martyrdom gave a greater “flavor” to the events of Otranto over the centuries, creating numbers and details of religious connotation, to strengthen Catholic morality against an Ottoman Empire that had just taken Constantinople and later, in alliance with Christian kingdom annexed several portions of Eastern Europe, seeming unbeatable.

The “martyrs”, the most useful forms of political propaganda in Europe’s boiling religious era, were canonized and recognized by the Church several times, most recently by Pope Francis in 2013, becoming the patrons of the city of Otranto.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nancy Bisaha (2004). Creating East And West: Renaissance Humanists And the Ottoman Turks. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 158.

Ilenia Romana Cassetta, ELETTRA ercolino, “La Prise d’Otrante (1480-81), entre sources chrétiennes et turques”, in Turcica, 34, 2002 pp.255–273, pp.259–260:

Brancolini, Janna. “The Italian astrophysicist who solved the mystery of the martyrs of Otranto”, Kheiro Magazine, May 19, 2017

Palma, Daniele, El Turcho in Terra d’Otranto. Lo sciame bellico dal 1480 al 1816

Andrić, Ivo (1990). The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia under the Influence of Turkish Rule. Duke University Press. p. 42.