The origins of Vampires in the Ottoman Empire

11/20/2020Far from being invented in Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1897, vampire mythology was already very popular in the 16th century Ottoman Empire. Life-sucking creatures were known there in the different languages of the empire and local folklore such as upir, obur, vrykolas, hortlak, cadı, mechey, tecz, and strigoi, with the same characteristics known today in pop culture: living dead who rise from their tombs, possessed the ability to fly, super strength, hated the daylight, and fed on the vital fluid of their victims.

In the Ottoman caliphate, there were even vampire hunters, and incidents in which Islamic jurists had to deal with alleged cases of vampirism presented by frightened villagers. Defeating them with a stake, tearing off their heads and burning their bodies was also part of the combat in the sultan’s lands.

Origins

It is not known exactly which specific culture in the Empire would have given genesis to the “Ottoman vampire”, most likely a mixture of all of them, with Arab, Persian, Greek, Turkish and Slavic elements that can be identified in the way the creature would have been known in the first records in the 16th century judicial systems. However, they all have a “common Islamic denominator” that unites them. Its most probable root that would begin to appear in the popular imagination of the peoples of the Empire under different names, is that it originated in the figure of the gouls, a specific category of the jinns (geniuses) mentioned in the Qur’an, which in themselves have vampire traits such as absorb the vital force of humans through their food.

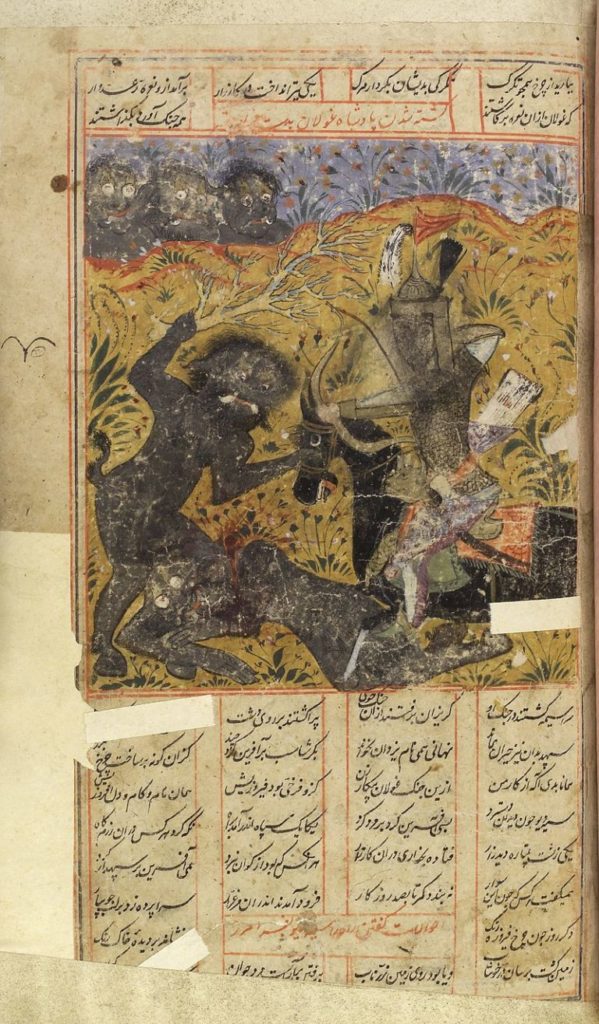

According to a certain interpretation of the Islamic scriptures, the gouls originated from the marid species of the race of the jinns who already had access to Heaven, from where they spied on divine decrees and returned to Earth to transmit occult knowledge to sorcerers. When Jesus, also a prophet in Islam, was born, three heavenly spheres were forbidden to them. With the arrival of Muhammad, the others were also forbidden to him. The marids then continued to try to ascend to heaven, but were burned by comets launched by Allah’s order, so that they could no longer deceive humanity through corrupt transmissions of what they heard in the heavens. If comets did not burn them to death, they were deformed and driven insane, falling into the wilderness, now in the form of gouls.

The gouls then started to live in cemeteries, feeding on the dead and living in a dark way, in a kind of vampirism. The goul figure started to influence the Muslim cultural imaginary, gaining several folkloric developments, now associated not only with the phantasmagorical-spiritual jinns of Islamic scripture, but also with human individuals linked to the somber, who wandered through cemeteries. They also appear in representations in the One Thousand and One Nights.

Vampires in the Shariah Courts

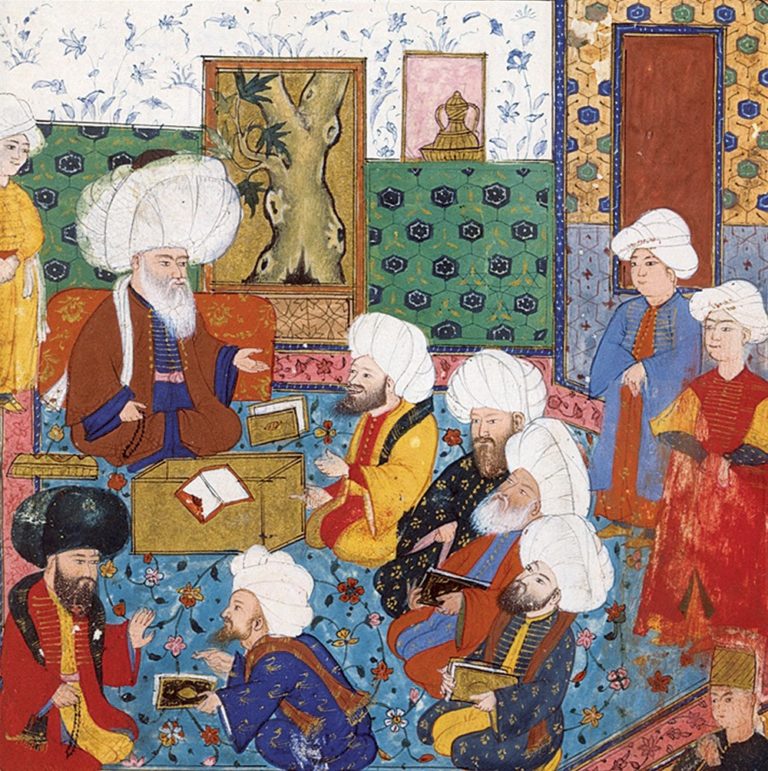

In addition to Islamic religion and cultural heritage, something that the Ottoman Empire took to the newly annexed Balkans since the 15th century was its folklore. There, in that ethnic cauldron, the Arabian goul, the Persian jadi (cadi) and the Turkish obur, mixed with local myths, and gave rise to the strange being that would arrive at the court of the grand mufti Ebussuud Efendi (1490-1574). According to reports at the time, villagers from the provinces of Rumelia (Balkans) and even Anatolia themselves, arrived at the court of Sheykh al-Islam (master of Islam) Ebussuud, the top Islamic religious authority of the Empire in the reign of Sulaiman the Magnificent, reporting something strange. The terrified peasants spoke of corpses rising from the pits, asborbing people’s lives, and when their graves were investigated, red streaks (blood?) were seen on their faces, and they were uncorrupted, in a position other than that which had been buried.

Skeptical about the veracity of the complaints, but wanting to calm the panicked people’s spirits, Ebussuud reported that he did not find in the sacred sources of the Islamic shariah something specific for such a creature, then suggested through a fatwa the following: if the corpse seemed to move, it should be nailed to the ground, if it were to rise again, it should have its head pulled out and placed on its feet. However, if he got up again, the body should be incinerated. Cases of vampires would continue to be reported in the court records of muftis in the Empire, mainly in the Balkan provinces, until the 19th century.

The legend of the vampires was even used by Ottoman state propaganda to defame the still resistant members of the Janissaries’ corps, the traditional military elite of the Empire finally annihilated in 1826, whose members even after death “returned to haunt the people”, leading to destruction of many of their graves.

In the travels of Evliya Çelebi

Another reference to vampires in Ottoman culture appears in the book Seyâhatnâme by the famous 16th century explorer Evliya Çelebi (1611-1682). Çelebi goes so far as to describe not only the creatures he called oburs (hungry), but also their “professional hunters”, paid to identify suspicious tombs and kill them:

The deceased’s relatives gave money to the oburs identifiers, who go to the tombs in search of the deceased who come out of the grave, identifying them through the disturbed soil. Immediately, people swarmed around them, and dug the grave of the hungry child, and then saw that their eyes were like cups filled with blood and their face with red blood from drinking human blood. (Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatname, Vol. XVII)

In the region of Abkhazia in the Caucasus Mountains, the explorer also gave more descriptions of the oburs, saying that he personally witnessed one levitate in the village of Pedsi, as well as talking about the method of incineration of the creature used by the villagers to destroy it.

The Vampire Crusade

In addition to villages throughout the Empire, the Ottomans also faced vampires on the battlefield. Without a doubt, the most well-known historical reference in the West associated with the figure of the vampire, who even inspired the character of Bram Stoker, is “Count Dracula” himself, or more specifically Vlad III Dracul (1431-1476), the Impaler. The 15th century Wallachian voivod made history as Romania’s national hero for his struggle against the Ottomans, emulating the ideal of a Christian crusade against an Islamic invader in the popular imagination of the region.

However, the far more extensive and less glorious part of the life of the Count of Transylvania was that he himself came to power with Ottoman support, was raised in the court of Sultan Murad II, betrayed his allies for self-interest, and established a sadistic regime in his country that lived up to his posthumous vampire fame. Vlad used to use impalement as a method of punishment for his captured enemies, that is, crossing living people with stakes, letting them die in an agonizing and extremely painful way. In the count’s life, reports of cannibalism, torture and cruelty even against his own Christian subjects abound.

His method of war against the Turks was treacherous, disguising himself as an equal and gaining the enemy’s confidence, promoting attacks from within, yielding garrisons just by posing as an Ottoman officer. Vlad’s years of terror ended in 1476, when ambushed by the forces of his childhood friend, Sultan Mehmet II, the Impaler was beheaded and his head sent to Istanbul. However, Vlad would not be the last “vampire crusader” enemy of the sultans.

Decades later, the Hungarian count Ferenc Nádasdy (1555-1604) raised the flag of the crusade and went down in history for his successive victories against Turkish expansion in the Kingdom of Hungary. However, like his former co-worker, he was known for also enjoying killing impaled people as a method of execution and macabre spectacle that fueled his sadism. But certainly, Ferenc was nobody when compared to his wife, the famous countess Elizabeth Báthory (1560-1614). Noble, refined, intellectual and rich, Elizabeth was certainly one of the most fascinating characters of her time, even taking part in the administration of her husband’s domains during the wars against Muslims (1593–1606).

However, the gentlemanly fame of the “pious noble anti-Islamic crusade” would fall apart, after successive denunciations by his servants, 300 witnesses more specifically. According to reports, the countess tortured and killed around 600 girls, using methods as horrifying as her husband’s and with goals that make her even more “vampire”. Bites, mutilations, cauterizations, and several other macabre ways of inflicting pain were applied by Elizabeth to her victims before death, who were then drained into her bloodbaths, which would “rejuvenate” her. After the denunciations were investigated, the sadistic countess was condemned by King Matias II of Austria to the perpetual prison in his castle, coming to die in 1614.

Conclusion

From the village to the battlefield, Ottoman culture is full of vampires, hunters of the living dead and “van-helsing imams”, however the legacy of this “Islamic” part of the legend is forgotten, submerged by the Gothic European Christian symbolism of crucifixes and holy water. In his research to create “Dracula” and the vampire universe in general, Bran relied on the work of Emily Gerard, who had published an article on “Transylvanian legends” in 1885, a Transylvania that had gained independence from the Ottoman Empire a few decades earlier, but was still loaded with its culture. More recently, Professor Dr. Salim Fikret Kırgı collected all the historical Ottoman references for creating the vampire legend in the book Osmanli Vampirleri – Söylenceler, Etkiler, Tepkiler (Ottoman Vampires – Rumors, Interactions, Reactions), still untranslated, but which opens a door to the academic study of the topic.