Osman Gazi: How a warrior’s dream created the Ottoman Empire

11/05/2020Osman I’s life, despite its historical importance, is still surrounded by uncertainties and doubts due to the scarcity of contemporary sources about him. Osman “Gazi” (warrior of the faith), whose date of birth is unknown, was the leader of the Ottoman Turks (osmanli, literally “from Osman”) and founder of the Ottoman Empire, from which his name and his royal house derive. Since there is no contemporary work about Osman that tells his life, it is difficult to distinguish what is factual or mythical about his story. Unfortunately, his life would not receive records until the 15th century, just over 100 years after his death. However, as the important 15th century Ottoman historian, Aşıkpaşazade, used to say, the economic concept of increasing value from scarcity can also be applied to history, so in that sense any document that presents information about the sultan’s life is still considered even more valuable.

According to Ottoman tradition, Osman was a descendant of the Kayi tribe and its lineage was derived from the legendary warrior Oguz Khan. The Kayi tribe, established in Anatolia1, was one of the many vassal Turkish tribes of the Seljuk Empire, and later would also play a fundamental role for the origins of the Ottoman Empire.

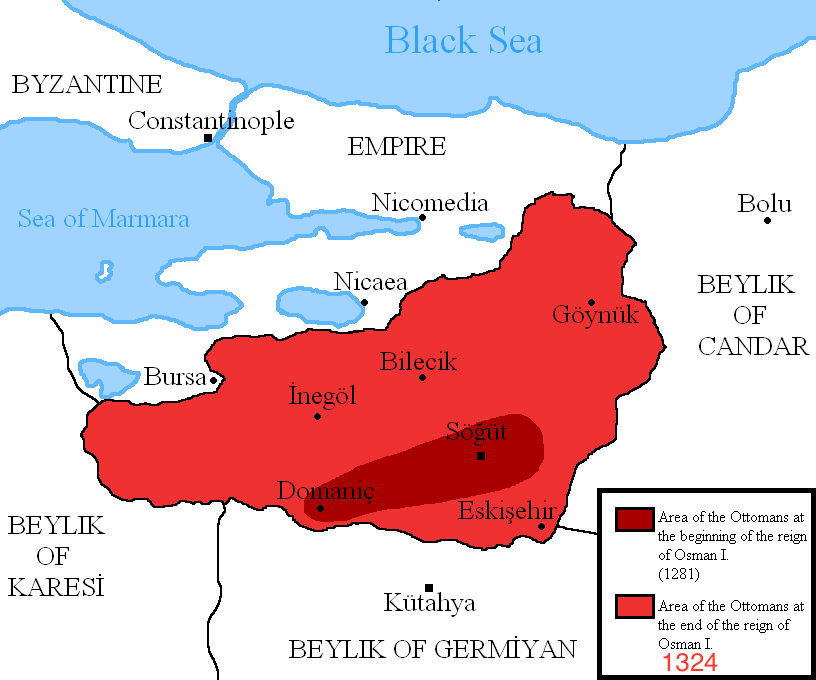

Osman became chief, or bey, after the death of his father, the legendary Ertugrul, in 1280. Thus, the Ottoman principality was one of several beyliks in Anatolia that eventually emerged in the second half of the 12th century, standing in the northern region of Asia Minor, more specifically in Bithynia, after the destruction of the Seljuks with the Mongol invasion. Due to the advantageous location, it was possible to carry out attacks in the already vulnerable Byzantine Empire, which later the descendants of Osman I would eventually conquer. The first event in Osman’s life on which it is possible to set a date was the battle of Bapheus, around 1301 or 1302, in which the founder of the Ottoman Empire defeated a Byzantine force that had been sent to fight him. In addition, Osman would also control the city of Söğüt and from there send attacks against his neighbor: Byzantium.

When Osman was still bey (lord) of a beylic he conquered an area equivalent to a small Anatolian city, which today would be equivalent to 1/3 of the territory of Bursa, in Turkey, which corresponds to 1,036 km². Osman’s sight, despite being a humble man, was certainly ambitious, and this can be clearly seen in his conquests, since he was not just an occupier who eventually plundered the city and left it by itself. This is something that can also be seen in the inheritance he left for his children2: horse armor, a pair of boots, some banners, a sword, a spear, a box of arrows, three flocks of sheep, a salt shaker and a box with a set of spoons.

Until the end of the 13th century, Osman’s conquests comprised the areas of Bilecik, Yenisehir, Inegol and Yarhisar, all in Turkey, as well as castles belonging to Byzantium in the respective areas mentioned.

An important factor in Osman’s conquests is that when he conquered the most significant territories of his legacy, the collapse of the Seljuk Turks’ authority also followed them, especially in the episodes of the occupations of the Eskisehir and Kulucahisar strongholds. The city of Yenisehir previously mentioned was the first significant conquest in the Seljuk territories, serving as the first capital of the Ottoman Empire.

At the beginning of the 14th century, more specifically in 1302, Osman achieved an important victory against the Byzantine forces near the city of Nicaea, thus beginning to establish his forces ever closer to the territories controlled by the Byzantine Empire, being an incessant threat until finally Osman’s successors conquered the Empire, capturing its capital Constantinople in 1453 by Sultan Mehmet II.

The Byzantines threatened by the sultan’s steady growth even tried to contain the Ottoman expansion, however in an uncoordinated manner and with a poor organization, resulting in only an ineffective attempt to stop the advance of the Ottoman forces.

The great sultan would also expand his kingdom in at least two directions, going north along the Sakarya River and southeast towards the Marmara Sea region, reaching his goals in an impressive way around 1308, a year that would also be marked by conquest of Osman’s followers from the Byzantine city of Ephesus, near the Aegean Sea, this being the last Byzantium city on the coast.

As for the last campaign of Osman’s life in the city of Bursa, although the sultan was not physically present in the battle, victory in Bursa was vital for the Ottomans, achieving an increasingly favorable position against the Byzantines.

It seems that Osman’s strategy was to increase his territory at the expense of the Byzantine Empire, all while avoiding conflict with more powerful Turkish neighbors. Thus, his first forays were through the passages that lead from the arid areas of northern Phrygia close to modern Eskişehir to the most fertile plains of Bithynia, achievements that were made possible by the defeat of the local Byzantine nobles, while at other times the environment would be different, for example through buying lands, marriage and other peaceful means or that simply just did not involve military disputes3.

Osman’s Dream

Osman was a humble man, but with great ambitions (in a good way). Not only, but he was also a very religious and deeply spiritual man, as can be seen in the posthumous descriptions of his life. The sultan had close relationships with the leader of the Sufi brotherhood of the Ahis, Sheikh Edebali, whose daughter Rabia Bala Hatun married Osman. One night, while sleeping at the sheikh’s house, the sultan would have his famous dream, which was narrated by Aşıkpaşazade as follows:

He saw that a moon arose from the holy man’s breast and came to sink in his own breast. A tree then sprouted from his navel and its shade compassed the world. Beneath this shade there were mountains, and streams flowed forth from the foot of each mountain. Some people drank from these running waters, others watered gardens, while yet others caused fountains to flow. When Osman awoke he told the story to the holy man, who said ‘Osman, my son, congratulations, for God has given the imperial office to you and your descendants and my daughter Malhun shall be your wife (FINKEL, p. 32, 2007).

There is also another famous description of the sultan’s dream, which follows:

Osman saw himself and his host reposing near each other.

From the bosom of Edebali rose the full moon, and inclining towards the bosom of Osman it sank upon it, and was lost to sight.

After that a goodly tree sprang forth, which grew in beauty and in strength, ever greater and greater.

Still did the embracing verdure of its boughs and branches cast an ampler and an ampler shade, until they canopied the extreme horizon of the three parts of the world. Under the tree stood four mountains, which he knew to be Caucasus, Atlas, Taurus, and Haemus.

These mountains were the four columns that seemed to support the dome of the foliage of the sacred tree with which the earth was now centered.

From the roots of the tree gushed forth four rivers, the Tigris, the Euphrates, the Danube, and the Nile.

Tall ships and barks innumerable were on the waters.

The fields were heavy with harvest.

The mountain sides were clothed with forests.

Thence in exulting and fertilizing abundance sprang fountains and rivulets that gurgled through thickets of the cypress and the rose.

In the valleys glittered stately cities, with domes and cupolas, with pyramids and obelisks, with minarets and towers.

The Crescent shone on their summits: from their galleries sounded the Muezzin’s call to prayer.

That sound was mingled with the sweet voices of a thousand nightingales, and with the prattling of countless parrots of every hue.

Every kind of singing bird was there.

The winged multitude warbled and flitted around beneath the fresh living roof of the interlacing branches of the all-overarching tree; and every leaf of that tree was in shape like unto scimitar.

Suddenly there arose a mighty wind, and turned the points of the sword-leaves towards the various cities of the world, but especially towards Constantinople.

That city, placed at the junction of two seas and two continents, seemed like a diamond set between two sapphires and two emeralds, to form the most precious stone in a ring of universal empire.

Osman thought that he was in the act of placing that visional ring on his finger, when he awoke.

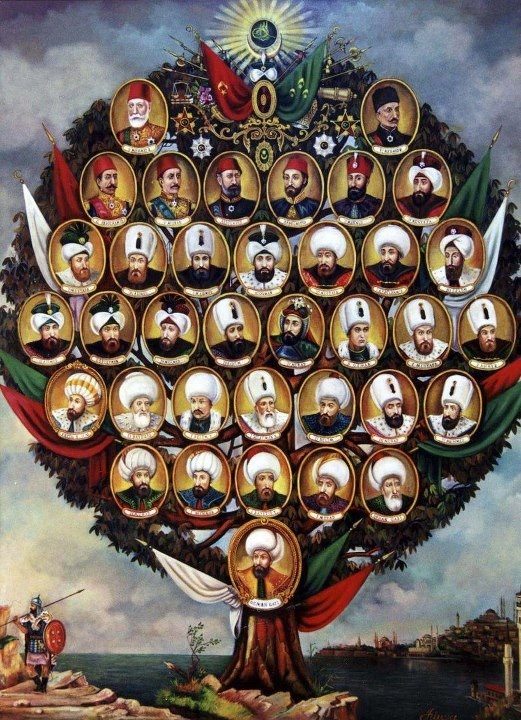

As can be seen from the above reports, as well as from the Ottoman Empire’s own history, Osman I’s dream would expand for more than six centuries, being one of the greatest empires in history.

His Death

The year 1324 (or 1323), when conquering Bursa, was also important due to Osman’s death. Because of his age and the increase of his illness, he placed his eldest son, Orhan, at the head of his troops. On his deathbed in Sogut, Osman lived long enough to hear from his son about Bursa’s surrender. According to the legend, Osman then gave Orhan his final advice:

My son, I am dying; and I die without regret, because I leave such a successor as thou art. Be just; love goodness, and show mercy. Give equal protection to all thy subjects, and extend the law of the Prophet. Such are the duties of princes upon earth; and it is thus that they bring on them the blessings of Heaven.

In recognition of the importance of victory, Osman then instructed Orhan to bury him in Bursa and make it the capital of the new Empire. Osman would die at 67 years old, and as requested, he was buried in Bursa in a beautiful mausoleum that would stand as a monument dedicated to the Sultan for several centuries after his death.

Notes:

[1] Present Turkey.

[2] Osman I had seven children, six men and one woman. It is interesting to note that Osman named his children based on the segments of society, being: Pazarlı (Merchant), Çobanm (Pastor), Alaeddin (servant of Allah), Orhan (leader), Melik (Master), Hamud (Praised). The sultan’s daughter was called Fatma Hatun.

[3] SHAW, 1976.

Bibliografia:

FINKEL, Caroline. Osman’s Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Basic Books. 2007.

ARSLANBENZER, Hakan. Osman Gazi: We are all living in his dream. Daily Sabah. 2017.

CREASY, Edward S. History of the Ottoman Turks: From the Beginnings of their Empire to the Present Time. Bentley. 1961.

STANFORD, Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. 1976.

KAFADAR, Cemal. Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. University of California Press. 1995