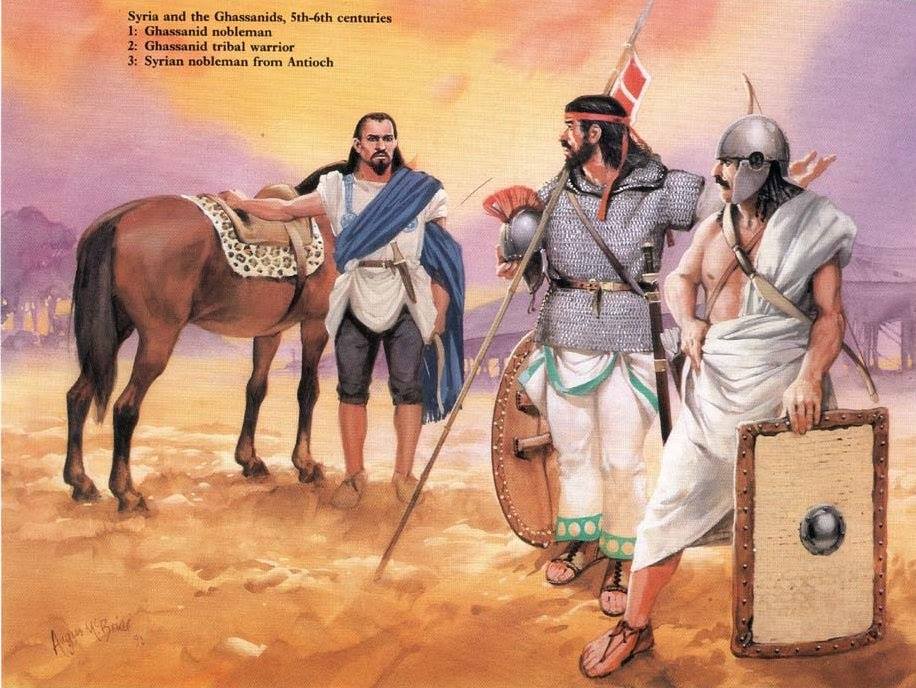

The Gassanid Christians and the beginning of the Byzantine Arab war

11/05/2020The Ghassanids, also known as Banu Ghassan (Sons of Ghassan) were a group of Arab Christian tribes who founded a kingdom of the same name. These tribes migrated in the early third century from what is now known as Yemen to Hauran, in Syria, where they would mix with Hellenized communities of early Christianity (ancient Christians). Because of this relation with Christians, within a few centuries they ended up converting to Christianity, even though many have already been christians as well.

After settling in the Levant region, the Ghassanids became vassals of the Byzantine Empire, which were rivals to the Persian Sassanid Empire. Because of this, the Ghassanids fought not only the Sassanids, but also against their vassals, the Lakhmids (Banu Lakhm), a Christian group that lived in the south of what is today Iraq.

After the Islamic conquest of Syria in the 7th century (634-638), some Ghassanids converted Islam, while the majority remained Christian, joining the Melkite and Syriac communities in modern regions of Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and also in Syria itself.

According to traditional historiography, the Ghassanids were part of the al-Azd tribe, migrating from southern Arabia, in present-day Yemen. Thus, they traveled across the Arabian Peninsula and settled in the Roman limes1. The date of migration to the Levant is uncertain, although it is known that it occurred in the 3rd century, and may vary between 250-300 AD, with some migratory waves around the year 400.

Some ancient accounts fit perfectly with the description of historians regarding the Ghassanid migration, such as the writings of Claudius Ptolemy, Pliny, the Elder and others. However, the oldest records regarding the Ghassanids are dated to 473 AD, due to an agreement between the Ghassanid leader, Amorkesos, and the Eastern Roman Empire. Such agreement recognized Amorkesos as foederati2, thus governing parts of Palestine.

Regarding the religiosity of the Ghassanids, they were not part of what could be called Christian orthodoxy, being first miaphysites and later, around the year 510 onwards, chalcedonians.

Relations with the Byzantine Empire

As previously stated, shortly after settling in the Levant region, the Ghassanids became vassals of Byzantium, a relationship that was very beneficial for the Byzantines, since they had an extra ally in the battle against the Sassanids and their Lakhmids vassals.

In this sense, due to the geographical position of the Ghassanid territories, which occupied a large part of the eastern region of the Levant, their lands also served as what is called a “buffer zone”3, again of great utility for the Byzantines, who thus ended up being protected from possible attacks by Bedouin tribes, one less threat to worry about.

The wars between Byzantium and the Sassanid Empire were many, and was in this context which the Muslim Empire ascended. As far as the Ghassanids are concerned, they were responsible for safeguarding trade routes, policing the Lakhmids tribes (allied with the Persians) and also providing troops when necessary for the Byzantine army.

Relations between Byzantium and Ghassanids were good in general, with the Ghassanid king al-Harith ibn Jabalah supporting the Byzantines in one of the countless wars against the Sassanid Empire, and in 529 was granted by Emperor Justinian I highest imperial title, which had never been granted to a foreign ruler before, and being also given the title of patrician to the Ghassanid king. However, later on there would be some disagreements between the Ghassanids and the Byzantines involving religious issues, since al-Harith was a miaphysite Christian, even helping to revive the Syrian Miaphysite Church, also supporting the development of this unorthodox doctrine, which by the way was the opposite to the theological views of Byzantium, who considered it to be heretical. Later the Byzantine Empire would pursue this religious heterodoxy, overthrowing even the successors of the aforementioned king, al-Mundhir and Numan.

Despite these religious disagreements, the Ghassanids still prospered economically, carrying out various religious constructions and public buildings, as is customary in empires and reigns in good economic circumstances. Due to the finances of the Ghassanids, they also invested in the arts, bringing famous poets to their courts, such as Nabighah adh-Dhubvani and Hassan ibn Thabit. The second was even one of the companions of the Prophet Muhammad, writing poems in his defense.4

Ghassanids and Islam

The Ghassanids were still vassals of the Byzantine Empire when Islam emerged and began to expand in the Arabian Peninsula. After the battle of Yarmuk in 636, a few years after the death of the Prophet, the Byzantines and the Ghassanids were to be overthrown by Muslims in Arabia.

The religious differences within the Ghassanid context certainly helped to divide them, weakening them before the Muslims. Thus, some were Chalcedonians, others Miaphysites, some even allying with Muslims (being Christians) because of the Arab identity in common with the faithful of Islam.

One of the main moments of contact between Ghassanids, Byzantines and Muslims was when the first provoked an attack of the Muslims against the Byzantines. Such Muslim reprisal occurred because the Ghassanids had killed a Muslim emissary sent by the prophet Muhammad. The Prophet had sent his emissary to the ruler of Bosra, southern Syria, but he would be killed by the Ghassanids in way to Bosra, in the village of Mutah under orders from a Ghassanid official.

Because of this diplomatic affront, Muhammad sent about 3,000 men in 629 to carry out a quick attack on the tribes responsible for the death of his emissary. The Muslim army was led by Zayd ibn Harithah, Muhammad’s adopted son. The second in command was Jafar ibn Abi Talib, nephew of the Prophet and Ali’s older brother, the third in command was Abd Allah ibn Rawahah.

It turns out that the Byzantine vicarius5 knew of the Muslims’ plans, thus organizing his army to wait for the Prophet’s men. Muslims heard about the extent of the enemy’s army on the way to the battle, which led them to reconsider their decision to move on, waiting for support from Medina. However, the third leader in command, Abd Allah ibn Rawahah told his companions that they wanted martyrdom, so there was no need to wait for reinforcements, because what they wanted was already right before them.

The Muslim army first encountered the Byzantines in the village of Musharif, withdrawing to Mutah, where in fact the two armies would fight. According to some Islamic sources, the battle was fought in the middle of two heights, diminishing the numerical advantage of the Byzantines over the Muslims. However, despite this strategy, Muslim leaders were defeated one by one, following their order of command: first Zayd ibn Harithah, then Jafar ibn Abi Talib and then Abd Allah ibn Rawahah.

After the fall of the three Muslim leaders, the army despaired. However, Thabit ibn Al-Arqam, seeing the soldiers’ despair and their low morale, took the army’s banner for himself, gathering the Muslims and saving them from the most complete annihilation, which would be certain if it were not for the intervention of al -Arqam, due to the chaos that had been established in the ranks of the Islamic army. After that, the army banner would be passed on to the new leader, Khalid ibn Walid, the legendary Muslim general, who recounted breaking nine swords during the battle of Mutah due to the intensity of the clashes. Khalid prepared to withdraw while facing the Byzantines in skirmishes, avoiding battles in tight places where they could be cornered.

Upon arriving in Medina, they were berated for withdrawing by, which caused the Prophet to order them to stop the reprimands. Later, Islamic tradition would mention that Khalid ibn Walid would have been called Saifullah, which means “The Sword of Allah”.

The Prophet would die in 632, being succeeded by Abu Bakr, who had definitive control over the entire Arabian Peninsula, resulting in a powerful Islamic state throughout the peninsula. A few years later, Muslims would be expanding more and more, conquering Syria, until then Ghassanid territory.

After this conquest, most of the Ghassanids still professed the Christian faith, whether it was a Melkite or some other Christian denomination, such as the Syriac Church. It is interesting to note that after the fall of the Ghassanids in the 7th century, several dynasties over the centuries took the title of successors to the House of Ghassan, such as the Nikephorian Dynasty of Byzantium and other rulers.

A curious factor is how dynasties centuries after the fall of the Ghassanids still continued to reclaim their legacy, like the rasulids sultans who ruled Yemen from the 13th to the 15th century, or even the Burji Mamluks sultans of Egypt from the 14th to the 16th centuries. It is worth remembering that the two dynasties mentioned were Muslims, whereas the Ghassanids had been Christians, but the claim to be part of the descent of the Arab nobility of the Byzantine time was certainly something that conferred status for those who affirmed it, even almost a thousand years later.

The Ghassanid legacy could still be seen until recently, since the last rulers who reclaimed the titles of successors of the House of Ghassan were Christians from Al-Chemor and Mount Lebanon, ruling the small sovereign potentate of Zgartha-Zwaiya until 1747.

NOTES

[1] Set of Roman boundaries and fortifications;

[2] Also called “Federates”, they were tribes associated with the Roman Empire through treaties, but did not have Roman citizenship or other similar benefits, but having the obligation to provide soldiers whenever necessary for the needs of the Empire if so requested. ;

[3] A strip of land separating one area from another;

[4] HOBERMAN, 1983;

[5] Local delegated authority;

BIBLIOGRAPHY

KAEGI, Walter E. Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

NORWICH, John Julius. A Short History of Byzantium. Penguin. 1998.

HOBERMAN, Barry. The King of Ghassan. AramCo. 1983.

ISHAQ, Ibn. The Life of Muhammad. A. Guillaume (trans.). Oxford University Press. 2004.