Banu Qasi: The Muslim dynasty of Visigoth origin

Autor: David Porrinas González 11/13/2020Text by: David Porrinas González

Confronted or allied with Christians or Muslims as convenience, the Banu Qasi will be an original product in a world where not everything was black and white, where there were different gray scales. The history of the Banu Qasi, as complex as it is exciting, is essential to understand the dynamics of change in the area of the Ebro and the genesis of what would later become the Kingdom of Navarra.

At the time of the Islamic conquest of Spain, there were some local lords who chose the path of submission, negotiation, capitulation or conversion to Islam to maintain their privileged situation. One of them was the famous Tudmir (Teodomiro), whose surrender to the Muslim conquerors to maintain his dominance in the area of Murcia and Orihuela we know thanks to the fact that they could be preserved in a kind of capitulation treaty that has reached us. Another of those Visigoth potentates who chose to become mawali (maulas in Spanish) was the little-known Count Cassius, of whom later chroniclers say he traveled to Damascus to pay his respects and submission to the caliph al-Walid, becoming his client, a kind of vassal, in exchange for continuing to hold power in territories that would eventually become part of the so-called Upper March of al-Andalus, which had its physical border in the Ebro and Zaragoza as the most important city. In this way, Count Cassius and his descendants will be important figures in a territory located in the middle valley of the Ebro, dominating the current regions of Navarra, Aragon and La Rioja. We know almost nothing about this Count Cassius, who some later Christian chronicle claims to have belonged to the “Goth nation“, but he embraced the religion of the Prophet Muhammad.

The first decades of the Banu Qasi family are somewhat bleak due to the scarcity of sources. The names of some of Cassius descendants are preserved, who were involved in different events of rebellion, at a time when the emirate power was in the process of consolidation and had to face several muladi uprisings. These years at the end of the 8th century and the beginning of the 9th century coincide with a growing presence of the Carolingian empire led by Charlemagne in the area between the Pyrenees and the Ebro, a region that would eventually be part of the domains of the Frankish sovereign, and which will be called “ Hispanic March”.

Musa ibn Musa, the “third king of Spain” (816-872)

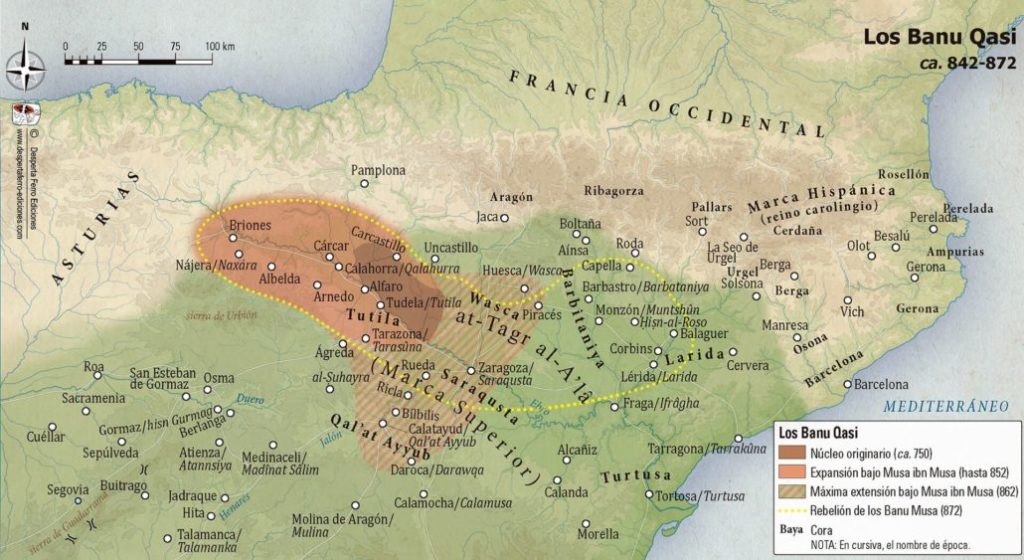

It will be at the beginning of the 9th century when the period of consolidation and heyday of the Banu Qasi begins, during the term of Musa ibn Musa, one of Count Cassius’ grandchildren. It must be said that Musa’s name has been quite recurrent in the family since the days of Count Cassius direct descendants, and that this would show a certain homage or reverence to the conqueror Musa ibn Nusair (c. 640-c. 716), with whom the visigoth count himself would have established the conditions for capitulation and submission to incipient Muslim power in the Iberian Peninsula. By the year 842, Musa ibn Musa’s power base would be located in the castle of Rioja de Arnedo. In that same year, Musa ibn Musa declared himself in rebellion against the emirate power of Abd al-Rahman II, and established a military alliance with his relative García Íñiguez, called Garsiya ibn Wannaqo by Islamic sources. Together they managed to defeat a punitive expedition sent from Cordoba and capture the leader of that emirate army. This news so irritated Abd al-Rahman II that he himself, accompanied by two of his sons, decided to lead a campaign to punish and subdue the Banu Qasi and Banu Wannaqo rebels. The punishment would take place in the spring of 843. After a devastating invasion, Abd al-Rahman II subdued Musa ibn Musa, naming him governor (wali) of Arnedo in exchange for the loyalty and release of the men who had been captured in the previous campaign.

The stability would not last long, because the following year Musa and his Basque relatives rose again against the emir, around Pamplona, being answered with a new fury that became a new submission. Meanwhile, Norman ships attacked Lisbon, Cadiz and Seville, forcing Abd al-Rahman to split his forces to respond to the intense Viking plunder. All of this would happen during the summer of 844, the moment of effervescence of the Scandinavian expeditions against the peninsular coast. And it is precisely Musa ibn Qasi that would be claimed by Abd al-Rahman to add his forces to the emirate army and face the Vikings. Once again, Musa would show his independent nature and military talent, separating from the emir’s host to organize a successful ambush against the Vikings near Morón de la Frontera.

It would not be long before Musa rose again against Abd al-Rahman II, followed by uprisings in the following years that caused the emir’s consequent armed response, at least twice, in the year 847 and the year 850. The priority objective of Musa with these rebellions was to take control of the important square of Tudela, something he would eventually achieve and that would lead him to reach his highest levels of power in the middle of the Ebro. The years 851-852 would be fundamental, since the deaths of Abd al-Rahman II and Íñigo Arista, the last uterine brother of Musa himself, and called Wannaqo ibn Wannaqo by Islamic texts. Between the years 852 and 859 Musa reached the peak of his power, being appointed governor of Zaragoza by the new emir, Muhammad I, and in fact acting as the maximum power in the middle basin of the Ebro, and making himself called, significantly, “the third king of Spain”, the others being the emir Muhammad and the Asturian monarch Ordoño I. These two dates correspond to the “two battles of Albelda “, the first raising the muladi to the top and the second overthrowing him. Those years would be very favorable for Musa, constituting in Albelda a new base of his power, controlling Zaragoza and Huesca and articulating a kind of independent taifa in the valley of the Ebro, also making his son Lope governor of Toledo. During these years, he would establish diplomatic relations with the Carolingian rulers, receiving gifts and favors from them, ending up acting as “the third king of Spain”.

Perhaps this success led him to adopt increasingly arrogant behaviors, which led his traditional allies from Pamplona to abandon him and to draw ever closer to King Ordoño I. In 859 Ordoño I, defeated and humiliated by Musa in the first battle of Albelda, and the king of Pamplona García Íñiguez, joined forces to attack Musa ibn Musa. They divided their troops in two, besieging one part of Albelda and preparing the other to face Musa’s armed response. Christian hosts crushed those of Musa, who was seriously wounded in the conflict and forced to flee. Then they entered Albelda and plundered and destroyed even its foundations, thus erasing the proud city from the map that Musa ordered to be built as a sign of his new power. From then on, Musa ibn Musa could no longer act as a proud and independent prince, even being abandoned by his son Lope, recently appointed governor of Toledo, who realized that times were changing and that it was better for him to get closer to the victorious and expansive Ordoño I.

The defeat at Albelda gave impetus to the Asturians and Pamplona, and Musa was forced to submit to Emir Muhammad I and ask for his help against Christian enemies who were increasingly pressing their dominions in the Ebro Valley. In 860, Musa was removed from his position as governor of the Upper March, and two years later, in September 862, he died in Tudela, as a result of a blow received during a confrontation with his son-in-law in Guadalajara a few weeks earlier. Alberto Cañada Juste, one of the authors who deepened the study of Musa ibn Musa and the Banu Qasi family, considers the character’s defining characteristics “a mixture of rebellion, loyalty at times, disloyalty when it was convenient, ambition, arrogance and above all a infallible courage”. All these qualities, and his particular life trajectory, make Musa ibn Musa a very attractive character, which even gave rise to a trilogy of historical novels based on his life and that of his family, published since 2009 by the Tudelan writer Carlos Aurensanz.

The lion cubs. The sons of Musa ibn Musa (Banu Musa)

The setbacks suffered by Musa in his last years led to a situation of submission of his children to the power of Cordoba. Two of them had fallen as hostages to Muhammad I. Thus, the decade between 862 and 872 would be marked by Banu Musa’s submission and obedience to the Emir of Cordoba. However, during these years the Banu Musa would not forget their father and the work he built, and would begin to maneuver to recover what was lost, getting closer and closer to the Christian king Afonso III, evaluating the possibility of rising again against Emir Muhammad. It will be between the end of 871 and the beginning of 872 when a new rebellion organized by the Banu Musa, Lope, Fortún, Mutarrif and Ismail, led by Lope, the eldest of the brothers, who had been governor of Toledo in the life of his father and thanks to him. From their emblematic fort in Arnedo, Lope and his brothers soon managed to seize important places in the Upper March, such as Zaragoza, Huesca and Tudela. This speed was possible because the brothers knew how to divide their forces to attack the aforementioned positions in a parallel and coordinated way, also counting on the support of the king of Pamplona, García Íñiguez, who was his brother-in-law, due to the marriage with his sister Oria Banu Musa. All these factors, in addition to speed, surprise and some other mistakes, were fundamental elements that explain how the Banu Musa managed to reach such important places in a few days. Banu Musa thus came to dominate the Upper March, controlling important enclaves such as Zaragoza, Huesca, Tudela, Monzón, Arnedo and Viguera.

It is not surprising that the reaction of Emir Muhammad I was not long in coming. Irritated by the rebellion and the consequent loss of control in the area, he empowered and rewarded the Tuchubíes clan, men of his trust and Arab lineage, to act in positions such as Calatayud and Daroca, located in the southern reaches of the rebels, constituting these places that should be reinforced and fortified to prevent a possible expansion of the Banu Musa to the south. Daroca and Calatayud, therefore, will become essential operational bases from which the Tuchubíes loyal to Muhammad I will fight against the rebels. The Emir complemented these preliminary provisions by organizing a military campaign of punishment and submission that he himself would lead in the spring of the following year. Even in favor of sending his children on these expeditions, Muhammad I understood that the seriousness of the events required his physical presence in the area, commanding a powerful army that would devastate the lands of the Banu Musa and, incidentally, also those of his allies in Pamplona.

Although this campaign served the emir to capture Mutarrif Banu Musa, control Huesca and, in some way, recover lost honor, it would be the years that would end most of the Banu Musa. Thus, Mutarrif and some of his sons were executed by order of Muhammad I in September 873; in the spring of the year 875, it was the eldest of the brothers, Lope, who found death, as he lost his arm while hunting deer, and that serious wound ended with his life. Fortún would remain ruling Tudela, and Ismail, as the only survivors of the line of Musa ibn Musa. It must be said, however, that not all scholars agree with the fact that Fortún survived his other brothers. What we do know for sure is that Ismail will act as the leader of the family, residing his power in Zaragoza, an important city that managed to resist some attacks launched by the troops of Muhammad I and his faithful, remaining in this situation until it is sold to the emir of Cordoba in the year 875. From that moment Ismail will base its power in positions like Lérida and Monzón, after years of relative tranquility in the region, coinciding with the intensity of the muladi revolts that were beginning to develop in the south of the peninsula.

In the summer of 886, Emir Muhammad I died, being succeeded by his son al-Mundir. In his brief two-year term, al-Mundir had to face an intense Muladi rebellion led by Umar ibn Hafsún from the impregnable fortress of Bobastro, in the mountains of Malaga, an eagle’s nest before which walls the emir was seriously wounded, dying as result of these wounds. In 888, the late al-Mundir was succeeded in the emirate by his brother Abd-Allah, who would have to face the most difficult phase of the revolt led by Ibn Hafsun. The need to concentrate his efforts in the fight against the Muladi rebels will bring a period of tranquility and independence to the Upper March, taking advantage of this situation Muhammad ibn Lope, Musa’s grandson, and Ismail ibn Musa, Musa’s only surviving son, both belonging, therefore, to the Banu Qasi family, controlling respectively the western and eastern sectors of the traditional family domains. This situation would slow the advance of Christians, especially in Pamplona, not because the Banu Qasi wanted to fight on behalf of Emir Abd-Allah, but because this resistance was essential for the preservation of their assets and their independence.

In the year 889, Ismail ibn Musa, the last of the sons of Musa ibn Musa the Great, died in Monzón, old and crippled. Their domains in Barbitania, a region located between the current provinces of Huesca and Lleida, have decreased somewhat in their last years. From then on, the decline of a clan began to play an important role in the middle valley of the Ebro during an interval of almost two centuries. Muhammad ibn Lope will remain the only Banu Qasi in the area, trying to recover Zaragoza on different occasions over the course of eight years. The new clan of the Tuchibíes, created by Muhammad I to prevent the Banu Qasi from the positions of Daroca and Calatayud, now ruled in Zaragoza coveted by the grandson of the great Musa ibn Musa. The Tuchibíes and Banu Qasi illustrate the gestation of family clans anchored in territories, some of genuinely Arab origin and others of Muladi origin, presenting different dynamics in the configuration of the mutations of local powers in the Islamic world of the emirate. It would be in one of his attempts to recover Zaragoza when Muhammad ibn Lope would meet his death, in the year 898, having left his son Lope ibn Muhammad as lord of Toledo. Lope will take a military action against Barcelona, killing Wifredo el Velloso, count of Barcelona and Gerona, in one of his raids in 897. In 898 Lope traveled to the Jaén region to talk to the rebel muladi Umar ibn Hafsun, to join forces in fight against Emir Abd Allah of the Umayyads. This muladi coalition scares the Umayyad loyalists of the time, some of whom refer to Ibn Hafsun as “the chief criminal of the South” and Lope ibn Muhammad as “the outlaw of the North”. But the death of Lope’s father in the siege of Zaragoza forced his son to return to the Ebro valley, to lead the siege initiated by his father. Death fell on Muhammad by a spear struck surprisingly by a man from Zaragoza, with his head severed and sent to Cordoba as a gift to Emir Abd Allah. In Cordoba, the head of the fearsome enemy was exposed for eight days, only to be buried with the honors that this brave enemy of the emirate power deserved.

A young Lope will be at the forefront of the Banu Qasi clan and domains, surrounded by enemies, Christians and Muslims, everywhere. Pressured by the tuchibíes of the south, by Afonso III of the west, by the people of Pamplona of the north, the situation was complicated for a Lope for whom the dramatic death of his father had been a blow. Even so, in the early years of the 90s of the 9th century, he managed to defeat an army of Afonso III in Tarazona and control the government of Toledo, returning an important city of the Tagus, former capital of the Visigothic kingdom, in the hands of the Banu Qasi family. Thus, four generations of the Banu Qasi, of Musa ibn Musa, were lords of Toledo. However, this control of Toledo was short-lived, and Lope had to face new ones launched in his lands in La Rioja and Álava by the Asturo-Leonese king Alfonso III.

The death of Lope ibn Muhammad and the slow agony of the Banu Qasi clan (907-924)

In those years Sancho I Garcés ascended the throne of Pamplona, becoming yet another enemy of the last great leader of the Banu Qasi. In the summer of 907, Lope ibn Muhammad attacked the the habitants in the same capital, Pamplona. Having camped near the city, Lope fell into some ambushes set up by the troops of Sancho Garcés I, dying in one of those traps, similar to others that had given Lope himself such good results in the past. Since then, the decline of the Banu Qasi family was unstoppable. The clan gradually lost possession, as the death of its leader gave wings to its enemies, who took advantage of the moment of confusion and weakness to occupy important places of the Banu Qasi. He would be in charge of Lope brother Abd Allah, preserving assets in La Rioja, Navarra Ribera and the Tarazona area, maintaining submission to the emir of Cordoba and occasionally facing the king of Pamplona Sancho I Garcés. In one of these clashes, in the year 915, Abd Allah was captured by the men of Sancho I Garcés, to be released by his brother Mutarrif after paying a ransom to the Basque king. Two months later, Abd Allah would die in Tudela, according to a Muslim author, as a result of a poison that was supplied to him while he was imprisoned by the king of Pamplona.

From then on, a process of disintegration of the lordship of the Banu Qasi, divided between brothers and children of the late Abd Allah, began. The time has come for expansive powers on both sides of the diffuse borders that separated the lands of Christians and Muslims. In the year 912, Abd al-Rahman III became the emir of Córdoba and from 915 he was able to serve the unstable northern borders of the emirate. A year earlier, Ordoño II had ascended the throne of Asturias, a king who, in addition to residing in the capital of the kingdom in the city of Leon, would carry out an expansive military policy. Sancho I Garcés of Pamplona will do nothing but move away from the Banu Qasi, becoming the main scourge of a dynasty condemned to disappear. Thus, by the year 923, the king of Basques and Pamplona had liquidated the last leaders of the Banu Qasi clan, conquering some of their most important positions in different military campaigns.

Chronicler Ibn al-Qutiyya summarizes the keys to the beginning of the extinction of the lordship of the Banu Qasi, saying that:

The Banu Qasi, increasingly, went from marasmus, from bad to worse, especially since Sancho, from Pamplona already dared with them, wanting to dominate them, until finally Abd al-Rahman, son, ascended the throne of Muhammad. (Ibn al-Qutiyya: Tarij iftitah al-Andalus. History of the conquest of Spain, p. 98).

Indeed, these successes by Sancho I Garcés motivated Abd al-Rahman III to accelerate the preparations to launch an intense attack against Pamplona. Thus, in April 924, a huge army commanded by the emir left Cordoba towards the north. That campaign devastated the lands of Navarra and destroyed Pamplona. Upon returning from that devastation, the emir stopped in Tudela and dismissed the last Banu Qasi, taking them with him to Cordoba to serve him in his armies. He handed Tudela over to the Tuchubíes de Zaragoza, that Arab clan that had shown so much loyalty to the emirs of Cordoba since the time of Muhammad I. In this way, Abd al-Rahman III, a self-proclaimed caliph five years later, ended two hundred years of a muladi which functioned as a kind of buffer state for the emirs of Cordoba in the face of the beginnings of Christian expansion and as a protective barrier against an incipient kingdom of Pamplona against Muslims. In fact, the genesis of what would later be called the Kingdom of Navarra cannot be understood without the existence of this Banu Qasi fiefdom, related to al-Andalus and Pamplona and, in a way, autonomous from all.

Abd al-Rahman III had not yet finished subduing the Muladi sons of Umar ibn Hafsún in al-Andalus, and he needed to understand that the Muladi landlords the only thing they gave their ancestors were many problems in the form of rebellions and wars that eroded the emirate power, and that forced him to concentrate efforts and resources against them. Thus ended the historic journey of a dynasty that knew how to navigate between two waters, that of the Basque lords, who were related to them several times, and the Muslim emirs of the south. Musa ibn Musa, the self-proclaimed “third king of Spain”, the most important figure in the history of the Banu Qasi, had laid the groundwork for a mestizo and quite autonomous landlord in the middle of the Ebro valley, and his successors managed to survive several decades thanks to the charisma and military leadership of its leaders, taking advantage of the weaknesses existing on both sides of the changing and unstable borders.

BIBLIOGAPHY

Cañada Juste, Alberto: “Los Banū Qāsī (714-924)”, Príncipe de Viana, 41 (1980), pp. 5-95.

De la Granja, Fernando: “La Marca Superior en la obra de al-‘Udrī”, Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragón, 8 (1940), pp. 447-545.

Guichard, Pierre: Al-Andalus. Estructura antropológica de una sociedad islámica en occidente, Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1995.

Ibn Hayyán: Crónica de los emires Alhakam I y Abdarrahman II entre los años 796 y 847 (Muqtabis II-1), trad. F. Corriente Córdoba, Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Islámicos y del Próximo Oriente de la Alfajería, 2001.

Ibn Hayyán: Anales de los Emires de Córdoba Alhaquém I (180-206 H. / 796-822 J.C.) y Abderramás II. Muqtabis II, (206-232 / 822-847), Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1999.

Ibn Hayyán: Al-Muqtabis III: crónica del emir Abd Allah I entre los años 275 H./888-889 d.C. y 299 H./912-913 d.C, Madrid: Publicaciones del Instituto Egipcio de Estudios Islámicos, 2017.

Ibn Hayyán: Cronica del califa ʻAbdarraḥmān III an-Nāṣir entre los años 912 y 942 (al-Muqtabis V), Zaragoza: Anubar: 1981.

Ibn al-Qūtiyya: Tārīj iftitāh al-Andalus. Historia de la conquista de España por Abenalcotía el Cordobés, J. Ribera (trad.), Madrid: Tipografía de la revista de Archivos, 1926.

Lorenzo Jiménez, Jesús: “Los husun de los Banu Qasi: algunas consideraciones desde el registro escrito”, BROCAR, 31 (2007), PP. 79-105.

Lorenzo Jiménez, Jesús: “Algunas consideraciones acerca del conde Casio”, Studia Historica, Historia Medieval, 27 (2009), pp. 173-180.

Lorenzo Jiménez, Jesús: La dawla de los Banu Qasi. Origen, auge y caída de una dinastía muladí en la frontera superior de al-Andalus, Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), 2010.

Lorenzo Jiménez, Jesús: “El valle del Ebro a través de los Banu Qasi”, Villa 3. Histoire et archéologie des sociétés de la vallée de l’Ebre (VIIe-XIe siécles), Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Mirail, 2010, pp. 217-240.

Pavón Benito, Julia: “Muladíes. Lectura política de una conversión: los Banū Qāsī (714-924)”, Anaquel de Estudios Árabes, 189/17 (2006), pp. 189-201.

Source: Desperta Ferro